The Quiet Legend: How Hilton Smith Shaped Baseball History in Wichita and Beyond

⋅ History

From a Bismarck boxcar to Cooperstown: The overlooked genius who helped integrate baseball

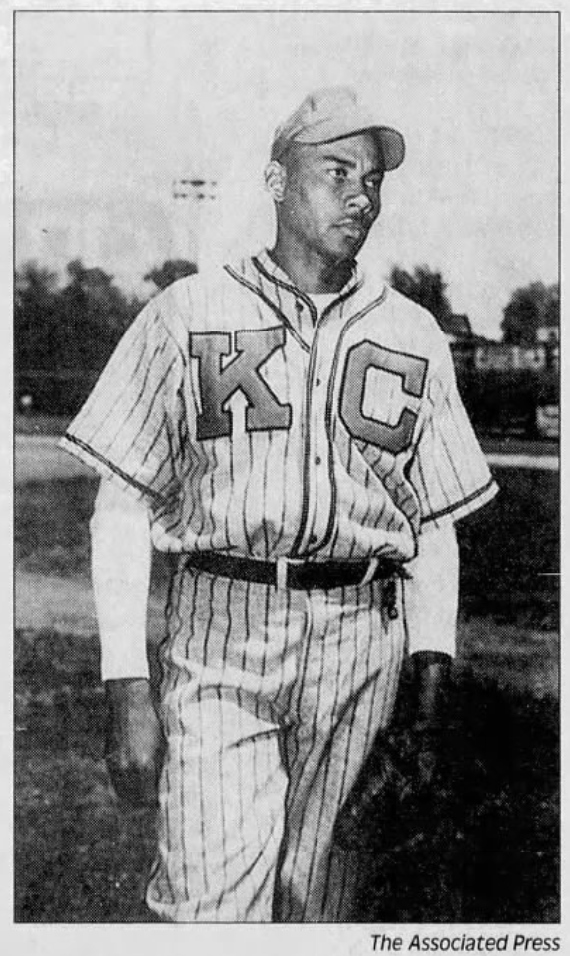

The plaque at the National Baseball Hall of Fame describes Hilton Smith as “a quiet and confident righthander.” For a man who spent most of his career in the shadow of Satchel Paige, pitching the final six innings after his flamboyant teammate worked the crowd through the first three, those five words capture everything about how he approached the game—and life.

Smith never sought the spotlight. He tutored illiterate teammates on long bus rides. He recommended Jackie Robinson to Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson years before Branch Rickey came calling. He dominated hitters with what Buck O’Neil called the greatest curveball he’d ever seen, then went home without bragging about it.

But for two remarkable summers in the mid-1930s, playing for an integrated semipro team in Bismarck, North Dakota, Smith got a taste of what baseball could become a dozen years before Robinson broke the major league color line. And at the inaugural National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita in 1935, then again in 1936 when he carried the team on his back, Smith proved he belonged among the game’s elite.

His induction this month into the NBC Hall of Fame, alongside his 2001 enshrinement in Cooperstown, finally places him where he always belonged: front and center in baseball history.

From Giddings to Monroe

Born in 1907, in Giddings, Texas, Hilton Lee Smith was the oldest of six children. He learned baseball from his uncles while helping raise his siblings, always playing against older competition—experience that likely accelerated his maturity on and off the field. At Prairie View A&M in the late 1920s, he studied Agricultural Science while transitioning from outfielder to pitcher.

His love for the game pulled him toward a professional career, and after college he bounced through various semipro teams before landing with the Monroe Monarchs in Louisiana in 1932. In 1932 he reportedly went 31–0 for the Monroe Monarchs, leading them to a Negro Dixie League championship. As he developed an arsenal of six pitches—including a devastating curveball that would become his signature—he also spent road trips teaching teammates to read.

By early July 1935, Smith was an established ace for Monroe. But everything changed when the Monarchs barnstormed through North Dakota.

Churchill’s Dream Team

Neil Churchill was a Bismarck car dealer with an obsession: assembling the best baseball team in America, regardless of race. In 1933, he’d already lured Paige and several other Negro League stars to play alongside white minor leaguers, creating one of the few integrated teams in the country. By 1935, Churchill had his sights set on the first National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, and he needed more pitching.

When the Monroe Monarchs stopped in Bismarck on July 8, 1935, Churchill offered Smith $150 a month to join immediately. Smith accepted. The next day, in Langenberg, Canada, he made his debut on the back end of a tripleheader—and in a twist of baseball fate, started ahead of Paige. Smith threw five scoreless innings before Paige relieved him for three more shutout frames. The game was called due to darkness.

Teammates would later nickname Smith “Satchels Relief” because he so often finished games Paige started. But on his very first outing with his new club, he’d been the starter.

Smith quickly proved his worth at the plate too. In his home debut against the Mexican All-Stars—then considered “the best baseball team on the road”—he went 2-for-4. His curveball, sometimes called “the old silencer,” helped him win at least five games during the short run-up to the NBC tournament.

Bismarck arrived in Wichita riding a 13-game winning streak. The city was buzzing about seeing Paige pitch as many times as possible in this new national tournament that sporting goods salesman Hap Dumont had dreamed up. Dumont had offered Paige $1,000 to bring his team—an enormous sum he didn’t actually have, betting he could make it at the gate.

The 1935 Tournament: A Supporting Role

In that inaugural NBC World Series, Paige delivered on Dumont’s gamble. He pitched in five of Bismarck’s seven games, striking out 60 batters and winning four times—a single-tournament record that still stands 91 years later. Chet Brewer, Churchill’s newest acquisition, threw the rest of the innings. Smith sat and waited.

His chance came in the semifinal against the Omaha Ford V-8s. In the first inning, Churchills centerfielder Quincy Trouppe injured his knee trying to stretch a triple into a home run. Smith entered as his replacement and seized the opportunity, going 3-for-5 with two doubles and three RBIs as Bismarck rolled to a 15-6 victory.

The next night, the usual cleanup hitter couldn’t play due to a hangover. Churchill thrust Smith into the fourth spot in the order. He responded with a 2-for-4 performance, driving in Bismarck’s first run and scoring their last as the integrated Churchills captured the first NBC championship, defeating the Duncan Cementers 5-2 to finish a perfect 7-0.

After the game, Trouppe was told by a scout that he could earn $100,000 playing ball “if he was white.” The color barrier stood firm, even as the Churchills had just demonstrated what integrated baseball could achieve.

1936: The Ace Steps Forward

Paige left Bismarck after 1935, but Smith stayed and blossomed into a complete two-way force. In his final start before the 1936 NBC tournament, facing the Kansas City Monarchs, he authored a performance that would change his life: a complete game allowing just two runs on five hits, plus a two-run home run in the eighth inning to tie the game before darkness ended it after nine innings.

Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson, always searching for talent just like Churchill, watched that game. He offered Smith $175 a month to join Kansas City after Bismarck’s season ended. Smith agreed.

But first, there was unfinished business in Wichita. Now the ace of the Bismarck staff with a chance to defend their title, Smith made an uncharacteristic promise to Churchill: he would match Paige’s four victories from the previous year.

He delivered. Over four outings, Smith dominated with three complete games, 25 strikeouts, and a perfect 4-0 record. When he wasn’t pitching, he hit .333 playing right field. But in the games Smith didn’t pitch, Bismarck went just 1-2, and they lost to the eventual champion Cementers in the semifinals. Had they won, Smith would have started the championship game.

For his performance, the NBC named Smith to the All-American team. As he left his hotel after the tournament, Hap Dumont pulled him aside with news: a couple of scouts were interested in signing him “if he was white.”

The reminder of baseball’s unbreakable color barrier might have crushed another player. Instead, Smith took it as motivation and headed to Kansas City to begin what would become a 13-year dynasty.

The Kansas City Years

Smith threw a no-hitter in the Monarchs’ 1937 home opener—a perfect game by his recollection, with only two balls hit out of the infield. It set the tone for a remarkable run. Between 1939 and 1942, he compiled a 93-11 record. He made seven consecutive East-West All-Star Games from 1937 to 1942. He helped the Monarchs win six pennants and the 1942 Negro League World Series.

O’Neil, who joined the team in 1938, didn’t mince words about his teammate’s ability: Smith possessed the greatest curveball O’Neil had ever seen, and “might have been the best pitcher in the world” from 1940 to 1946.

The stats support that claim. Smith won more than 20 games every season with Kansas City. He went undefeated in league play in 1938 and 1941. He hit .290 over his career, often playing outfield or first base when he wasn’t pitching. In exhibition games against white major league all-stars, he more than held his own—shutting out a team that included Bob Feller in 1937, and limiting the Yankees to one baserunner (Joe DiMaggio) over five innings in Venezuela in 1947.

“From 1940 to 1946, Hilton Smith might have been the greatest pitcher in the world,” O’Neil said. Fellow Hall of Famer Monte Irvin agreed: “He had one of the finest curveballs I ever had the displeasure to try and hit.”

Yet Paige’s shadow followed him throughout. When promoters wanted to draw crowds, Paige pitched the first few innings to bring fans through the turnstiles, then Smith worked the final six to actually win the game. Teammate Allen “Lefty” Bryant summed up the situation: “Hilton never got the credit he deserved. We never told him, but Hilton was our best pitcher, including Satchel.”

The Jackie Robinson Connection

Smith’s greatest contribution to the sport may have come in 1942, during an exhibition game between Black all-stars and white major leaguers. He met Jackie Robinson, then serving in the Army, and was so impressed that he immediately wrote to Wilkinson urging him to sign Robinson.

It didn’t happen at the time. Robinson was drafted into the Army and later faced a court-martial on trumped-up charges before receiving an honorable discharge in 1944. But when Robinson reached out to the Monarchs for a tryout, Wilkinson remembered Smith’s recommendation and signed him for the 1945 season.

Robinson hit .387 in 47 games for Kansas City. Branch Rickey saw him play, signed him to a Dodgers contract, and the rest is history. Without that chance encounter in 1942—without Smith recognizing Robinson’s talent and vouching for him—who knows if Robinson would have become the man to break baseball’s color barrier?

Smith himself was sometimes mentioned as someone who could have broken the color barrier, but by then he was nearly 40 and considered himself no longer at his peak. “I was too old at that point,” he said later. But he never expressed bitterness about being overlooked. That wasn’t his way.

The Legacy

After retiring in 1948, Smith became a schoolteacher and later worked as a foreman at Armco Steel in Kansas City. He scouted for the Chicago Cubs with O’Neil until his death on November 18, 1983, at age 76. His son DeMorris said his father wanted his legacy to be one of giving back to the game and those who came after him.

For years, Smith’s name appeared mostly in footnotes—the relief pitcher for Paige, the scout who recommended Robinson, the steady hand who won 20 games every season without fanfare. Friends and coworkers often expressed surprise when they learned of his Hall of Fame career. Smith rarely mentioned it.

The Veterans Committee corrected part of that oversight in 2001, electing Smith to the National Baseball Hall of Fame 18 years after his death. Now, with his induction into the NBC Hall of Fame, another piece falls into place.

The 1935 Bismarck Churchills were more than a curiosity. They were proof that integrated baseball could work, could win, and could thrill fans of all backgrounds. They won the very first NBC championship while Major League Baseball still had a dozen years before Robinson would don a Brooklyn uniform. And Hilton Smith was there for it all—contributing three hits and three RBIs in the semifinal and final, even if he never got to unleash that devastating curveball in tournament play that summer.

In 1936, when the pressure fell entirely on his shoulders, he delivered the performance of a lifetime: 4-0 with 25 strikeouts, a .333 batting average, and an All-American selection. He promised to match Paige’s four wins from the previous year. He kept his word.

That was Hilton Smith: quiet, confident, and utterly reliable. He tutored teammates who couldn’t read. He recommended the player who would change baseball forever. He possessed what may have been the best curveball in the history of the game.

And finally, 91 years after he first stepped onto a baseball field in Wichita, he’s getting the recognition he deserved all along.