The Man in the Panama Hat: How Hap Dumont’s Wild Ideas Changed Baseball

⋅ History

When Innovation Meets Tradition at the Heart of America’s Game

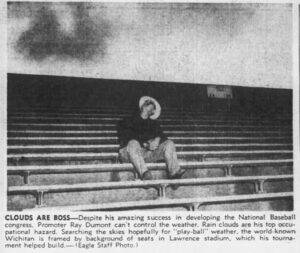

Raymond “Hap” Dumont wore a big Panama hat, chewed cigars, and refused to accept baseball as it was. While others saw tradition, he saw possibilities—faster games, better umpiring, glowing baseballs, and opportunities for players the major leagues ignored.

Some of his ideas failed spectacularly. Others took decades to prove their worth. A few changed baseball forever.

From testing an electric timer at a Negro League exhibition game to building a tournament that gave integrated teams a national stage years before Jackie Robinson, Dumont spent his life asking “what if?” when everyone else said “that’s not how we do things.”

The 20-Second Solution

The 20-Second Solution

Dumont tested his electric timer at an exhibition game between the Indianapolis Clowns and New York Stars at Lawrence Stadium. Games that once stretched past 2½ hours suddenly finished in under two hours. When he introduced it to the NBC tournament, attendance went up 29 percent and game length dropped an average of 25 minutes.

“The delightful fact is,” Dumont said, “that we had only 14 infractions in 64 games. Just the threat of a penalty kept the players hustling and the game fast-moving.”

The timer enforced simple rules: 90 seconds between innings, 20 seconds for pitchers to deliver, penalties for delays on either side.

“I was delighted with the reaction of the players and managers—they liked the hustle as much as the fans did,” Dumont said. “Even the cynical, old-fashioned major league scouts at the tournament liked it.”

Major League Baseball ignored the idea for 60 years. In 2023, MLB finally installed pitch clocks and saw the same results Dumont had documented in 1962: games shortened by 25 minutes, attendance increased, younger fans returned.

“Innovation is the foundation of the National Baseball Congress,” said current NBC director Katie Woods “You are talking about multiple ideas that were decades ahead of professional baseball, and in some cases decades ahead of the technology needed to pull them off, but somehow Hap could still see the vision and was willing to try.”

Ideas That Worked (Eventually)

Ideas That Worked (Eventually)

Dumont believed umpires shouldn’t have to guess on close plays. He experimented with what he called the “magic eye”—an electronic system using sensors to capture what human eyes might miss.

Baseball wasn’t ready. The suggestion that umpires needed technological help was treated as heresy.

MLB introduced instant replay in 2008 for home runs. By 2014, replay covered most plays. By 2024, automated ball-strike systems were being tested in minor league parks. The debate now isn’t whether computers can call balls and strikes accurately—they can—but whether baseball wants them to.

Hap was asking that question 80 years earlier.

“He was way ahead of his time then,” Larry Davis, who succeeded Dumont as NBC director, said decades later. “Technology hadn’t kept pace with him.”

Ideas That Didn’t Work (But Paved the Way)

Not everything Dumont invented was ahead of its time. Some ideas just didn’t work with 1930s technology—but they asked the right questions.

In 1936, he installed an underground microphone near home plate at Lawrence Stadium, operated by compressed air. This “rhubarb mike” captured arguments between managers, umpires, and players for fans to hear. Staff would tip off managers when the mike was live.

The contraption made so much noise that hitters jumped with fright the first time they heard it. The system eventually got ripped out of the ground when an umpire needed new baseballs—old habits die hard.

The system didn’t last, but Dumont had asked the right question: what if fans could hear what happens on the field? Today, MLB has players regularly wear microphones for live conversations with the broadcast booth during games. Pitchers like Clayton Kershaw get mic’d up on the mound during nationally televised games, and directional microphones around every stadium capture the sounds Dumont tried to bring to fans in 1936.

During World War II, Dumont painted baseballs with fluorescent paint until they glowed under the lights. Then he painted foul lines, gloves, bats, and cap bills with the same coating. He gathered local players to test it.

Without a contrasting background, the glowing ball seemed to float in space. Outfielders couldn’t judge depth. Infielders couldn’t track speed.

The “glo-ball” never caught on permanently, though Dumont tried again in the 1950s. But in 2021, Tri-City Chili Peppers owner Chris Martin noticed a kid with a glowing toy and thought, “What if the entire field was glow-in-the-dark?” That’s how Martin invented Cosmic Baseball. The team installs black lights around their stadium that emit ultraviolet light, making UV-reflective neon balls and fluorescent jerseys glow. Players report the glowing ball is “just a little brighter and easier to see” than regular night baseball. Cosmic Baseball now features UV-reflective neon balls and fluorescent jerseys played before screaming fans, and the concept has spread to ballparks nationwide.

Hap Dumont’s fluorescent baseballs failed in the 1940s. But eight decades later, glow-in-the-dark baseball is selling out stadiums.

The Real Innovation

Dumont’s greatest innovation wasn’t technological. It was the National Baseball Congress itself.

In 1931, Kansas semi-pro baseball was dying. The Depression had killed local leagues. Parks sat empty. The sporting goods department where Hap worked at Goldsmith Office Supply wasn’t selling anything.

Dumont launched the Kansas Semi-Pro Baseball Tournament, gathering 16 teams to play in Wichita. He promoted relentlessly, drew 1,500 fans, and almost single-handedly brought baseball back to Kansas.

By 1933, the tournament had outgrown Island Park. Hap told Wichita City Manager Bert Wells the city needed a new ballpark. Wells said the city couldn’t justify the expense for a state tournament.

Dumont said he wasn’t thinking about a state tournament. He was thinking national.

A week later, Wells called back. Wichita would build Lawrence Stadium. And Hap could have his national tournament.

The Gamble That Started Everything

It was 1935. Brand-new Lawrence Stadium awaited the first National Semi-Pro Tournament. To guarantee a draw, Dumont invited the Bismarck, North Dakota, team featuring Satchel Paige, the most dominant pitcher in baseball, barred from the major leagues because he was Black.

Paige would sell out every game he pitched. But his team wanted a $1,000 guarantee – the equivalent of about $23,000 in 2025. Dumont was broke.

He gambled. He told them they’d get $1,000—if the tournament made money. If it didn’t, they’d get nothing.

Paige’s team won the tournament. The gate receipts covered the guarantee with money left over.

From that beginning, the National Baseball Congress grew into a premier amateur baseball tournament, running continuously for 90 years.

The Experimental Spirit Lives On

Larry Davis remembered Dumont as someone who “really stayed in the background. He was an amazing man. He always said people didn’t come to see him, they came to see the ball game.”

But Hap understood something crucial: people came to see something worth watching. Baseball couldn’t rest on tradition alone. It had to evolve.

Some ideas failed. The glo-ball was absurd (until it wasn’t). Backwards base-running lasted one game. The rhubarb microphone had mixed results; and now you won’t see an MLB game without microphones.

But the pitch clock works. The magic eye works. The innovations that bring fans closer to the action work.

Dumont proved that honoring tradition didn’t mean refusing to change. He showed that amateur baseball could be a laboratory for ideas that might take decades to reach the major leagues.

The Man Behind the Hat

Decades after Dumont’s death, his pitch clock is in every major league ballpark. His magic eye is being tested in minor league games. His tournament still runs every summer.

Lawrence Stadium was renamed Lawrence-Dumont Stadium in his honor in 1978. After 84 years of service, it was demolished in 2018. The NBC World Series now takes place at Wichita State University’s Eck Stadium, with Championship Night held at Equity Bank Park—the new stadium built on the site where Lawrence-Dumont once stood.

The innovations that worked changed baseball. The ones that failed taught valuable lessons. All of them mattered because Hap created a space where trying something new was encouraged, not punished.

The man in the Panama hat was right about more than just pitch clocks. He was right that baseball could always be better. He was right that innovation requires the freedom to fail. And he was right that Wichita, Kansas, sitting in the heart of America’s heartland, was exactly the right place to prove it.

Supporting the NBC Baseball Foundation helps preserve the innovative spirit that has defined the tournament since 1935. From $19.35 for tournament supplies to $250 for the Hap’s Innovation level, every contribution ensures the NBC can continue honoring tradition while embracing the future—just as Hap Dumont intended.