From Magic Eye to ABS: How Hap Dumont’s 1941 Vision Became MLB’s 2026 Reality

⋅ NBCWhen Major League Baseball announced that the Automated Ball-Strike system would be implemented across all 30 teams beginning in 2026, most observers saw it as a revolutionary leap into baseball’s technological future. But for those familiar with the history of the National Baseball Congress, the development felt more like déjà vu.

Eighty-five years earlier, a cigar-chomping sporting goods salesman from Wichita named Raymond “Hap” Dumont was already envisioning a world where technology could eliminate the human element from calling balls and strikes.

The “Mechanized Baseball Man”

By 1940, Dumont had already earned a reputation as what one Associated Press writer called “the mechanized baseball man.” His National Baseball Congress tournament had become a proving ground not just for amateur talent, but for radical innovations that would reshape the game. He’d introduced automatic home plate dusters in 1939 to spare umpires from bending over between pitches. In 1940, he installed what newspapers called a “leaping microphone” system that amplified player-umpire arguments for fans’ entertainment.

But Dumont’s most ambitious project was what he termed the “Magic Eye” – a device that would use vertical beams of light to determine whether a pitch crossed through the strike zone. “The device is one in which vertical beams of light at home plate, when broken by a pitcher’s delivery, indicate that the ball is within the strike zone width,” explained contemporary newspaper accounts. The system was designed to help arbiters determine balls and strikes, though Dumont acknowledged from the start that it could eventually eliminate the plate umpire entirely.

“The device is one in which vertical beams of light at home plate, when broken by a pitcher’s delivery, indicate that the ball is within the strike zone width,” explained contemporary newspaper accounts. The system was designed to help arbiters determine balls and strikes, though Dumont acknowledged from the start that it could eventually eliminate the plate umpire entirely.

Innovation Meets Resistance

The reaction to Dumont’s Magic Eye perfectly predicted the debates that would surround automated strike zones decades later. Baseball traditionalists recoiled at the suggestion that technology could replace human judgment in America’s pastime.

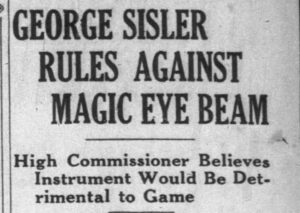

“I feel it is detrimental to baseball,” declared George Sisler, the Hall of Fame first baseman who served as high commissioner of semi-pro baseball, “because it is designed eventually to eliminate an essential part of the game – the plate umpire.”

Dumont’s response revealed his understanding of both innovation and public relations. Rather than defending the technology’s superiority, he emphasized its potential to enhance rather than replace human officials. The Magic Eye would assist umpires, he argued, not supplant them entirely.

Yet even Dumont seemed to recognize the ultimate trajectory of his innovation. When his engineers successfully perfected the system by late 1940, crossing “one magic eye with another” to create what newspapers described as an “iron umpire so effective it won’t be used for fear of creating unemployment among the boys in blue serge,” he made a telling decision. Despite having developed what appeared to be a functional automated strike zone system, Dumont chose not to implement it in regular play, citing concerns about eliminating umpire positions. The Magic Eye would be demonstrated at exhibition games only, a technological marvel relegated to curiosity status.

The Technology That Wasn’t Ready

Contemporary accounts suggest Dumont’s Magic Eye was more sophisticated than many realize. The system used crossed light beams to detect when a baseball passed through the strike zone, with the ability to distinguish between balls and strikes in real-time. Plans included photo-finish cameras to capture close plays and instant replay capabilities decades before MLB would embrace such technology.

“When a runner starts from third for home the button-puncher goes into action and the camera rises to record everything that happens within 10 feet of home plate,” explained one 1942 newspaper report. “On close plays, Dumont says, the films will be developed immediately, and at the feature night games the lights in the park will be turned off and the pictures projected, in slow motion, on a huge screen in the outfield.”

But the Magic Eye suffered from the same limitation that would plague automated strike zone technology for decades: defining the strike zone itself. While the system could detect horizontal boundaries with precision, determining the vertical limits of each batter’s individual strike zone remained problematic.

From Wichita to the World Series

What makes Dumont’s vision particularly remarkable is its context within the National Baseball Congress’s broader influence on professional baseball. The NBC tournament served as a laboratory for innovations that Major League Baseball would later adopt, from integrated rosters to night games to advanced statistical tracking.

Many of the technological concepts Dumont pioneered in Wichita – the pitch clock, instant replay, enhanced audio for fan engagement, photo-finish documentation of close plays – would eventually become standard throughout professional baseball. His Magic Eye represents perhaps the most prescient of these innovations, anticipating by eight decades the exact technological solution that MLB has now embraced.

The Long Arc of Innovation

The parallels between Dumont’s Magic Eye and MLB’s Automated Ball-Strike system extend beyond mere technology. Both innovations emerged from the same fundamental tension: the desire for increased accuracy and consistency in officiating versus respect for baseball’s human traditions.

Like Dumont, modern MLB officials have been careful to frame the ABS system as assistance rather than replacement, emphasizing that human umpires will retain control over the technology. The league’s gradual implementation plan – testing in minor leagues before full MLB adoption – mirrors Dumont’s cautious approach to revolutionary change.

Even the resistance patterns match. Critics of the ABS system echo George Sisler’s 1940 concerns about eliminating “an essential part of the game,” while supporters argue for the benefits of technological precision over human fallibility.

The Vision Vindicated

Perhaps most remarkable is how closely MLB’s 2026 implementation timeline matches Dumont’s original projections. In 1940, he suggested that widespread adoption of automated strike zone technology might take decades to achieve – a prediction that proved accurate to within a few years.

The National Baseball Congress continues to serve as a testing ground for baseball innovations, maintaining the experimental spirit that Dumont established in the 1930s and 1940s. While the Magic Eye never made it past the demonstration phase, its conceptual DNA can be traced through decades of technological development to the TrackMan and Hawk-Eye systems that will soon govern balls and strikes in major league parks.

When the first ABS-called strike crosses the plate at Yankee Stadium or Fenway Park in 2026, it will represent the fulfillment of a vision that began with a small-town innovator who believed technology could improve America’s pastime. Hap Dumont’s Magic Eye may have been ahead of its time, but time, as it turns out, was exactly what it needed.

The automated strike zone revolution didn’t begin in Silicon Valley or major league front offices. It started in Wichita, Kansas, with a man who understood that baseball’s future would be built on the foundation of its innovative past.

________________________________________

The National Baseball Congress continues to honor Hap Dumont’s legacy of innovation through its ongoing tournament operations and historical preservation efforts. One of the projects of the NBC Baseball Foundation 501c3 is to collect and maintain archives documenting Dumont’s technological experiments and their influence on modern baseball. You can support the NBC’s historical preservation projects at https://nbcbaseball.com/support/