Blue, Konopka, Cunningham and Hooper are the newest members

The National Baseball Congress announced the 2024 NBC Hall of Fame class, adding three new members to the prestigious group representing those with a lasting impact or contribution to the National Baseball Congress. The new inductees will be recognized on August 3rd at Eck Stadium in Wichita, Kansas during the 90th NBC World Series, powered by Evergy.

The 2024 National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame inductees are:

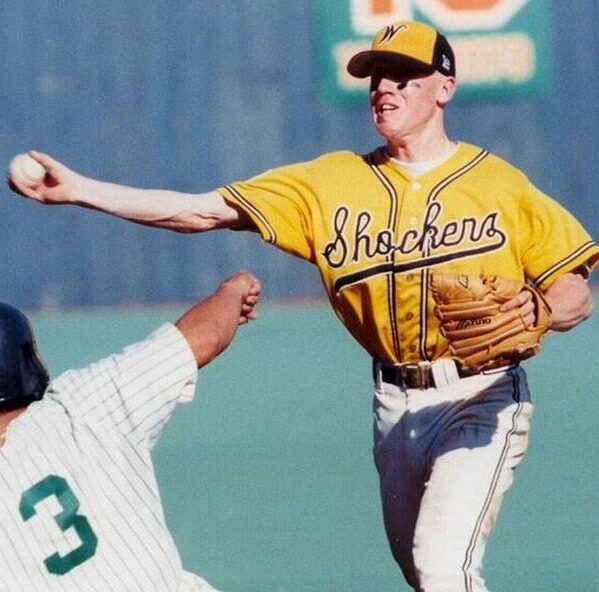

Kevin Hooper

Kevin Hooper played his high school baseball in Lawrence, KS before coming to Wichita State University in 1996. During his time at WSU, Hooper was a two time All-American and won a Golden Glove award in all four of his seasons. His first appearance in the NBC World Series came in 1996 when he played for the Liberal Bee Jays, where he hit .429. During the summer of 1998, Hooper played for the NBC World Series Champions El Dorado Broncos. Hooper was named to the 1998 NBC World Series All-American team as a second basemen. Hooper went on to play professional baseball and made his MLB debut in 2005 with the Detroit Tigers. After a brief stint in the Majors, Hooper came back to Wichita to play for the Wichita Wingnuts. After one season as a player, Hooper was named the manager and led the Wingnuts to a 422-270 record over seven seasons. Today, Hooper is back in professional baseball, currently serving as the Director of Player Development for the Atlanta Braves.

Mike Blue

Mike Blue was active in the NBC World Series from 1959 to 1968. Before his NBC days, Blue was a star pitcher and football player at West High School and then went on to play baseball at Wichita State University. As a player in the NBC World Series, he played for the Boeing Bojets, Wichita Rapid Transit Dreamliners and Cessna Bobcats. Blue played seven years of affiliated baseball for the San Francisco Giants and the Washington Senators. After his playing days, Blue helped coach the El Dorado Coors. Blue was a prominent figure in the public school system, teaching and coaching for 32 years at East and West high school. He retired from education in 2001 and passed away in late 2017. Blue is also a member of the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame and West High School Hall of Fame.

Myra Cunningham

Myra Cunningham came to Wichita in 1921 from Salina, KS where she graduated from the Salina Business College. Starting in 1934, the year before the first National Baseball Congress Invitational Tournament, she became the Secretary to Hap Dumont, the founder of the NBC World Series. Cunningham was the Secretary for 25 years until her sudden death in 1959. Myra Cunningham will be remembered as being instrumental in the start-up, success, and continuation of the NBC World Series.

Bruce “Bruno” Konopka

Bruce Konopka was a Major League Baseball player and War Veteran before ever stepping foot in Wichita, KS. After playing baseball at the University of Southern California, Konopka made the Major Leagues in 1942 with the Philadelphia Athletics. Konopka made appearances in the 1942 and 43 seasons, but Konopka was called to serve for the United States during WWII. Due to his service, Konopka missed the 1944 and 45 seasons. In 1946, Konopka returned to Athletics and played in 38 games. In 1947, Konopka came to Wichita, representing the Golden Colorado Coors in the NBC World Series. Konopka’s experience in the big leagues showed as he won the MVP of the tournament and helped his team finish second.

The 2024 NBC Hall of Fame induction ceremony will take place before the Championship game of the 90th NBC World Series, powered by Evergy, on August 3rd at Eck Stadium in Wichita. Tickets to the game start at $12, or $7 for groups of 10+ Click here for Championship Night Tickets. You can also purchase tickets to a special reception for the Hall of Famers in the All-American Club for just $45 including dinner. Click here for Hall of Fame Reception Tickets

About the NBC Baseball Foundation: The National Baseball Congress World Series has been a cornerstone of summer collegiate and independent baseball for over 89 years, providing a platform for players to showcase their talents and fostering a sense of community among baseball enthusiasts. The NBC Baseball Foundation strives to connect communities through baseball, and foster a love for the game while celebrating the history. The NBC World Series, powered by Evergy, will be held July 25-August 3 at Eck Stadium in Wichita. For more information about the National Baseball Congress, please contact: Katie Woods, Tournament Director at katie@nbcbaseball.com or 316-265-6236 or visit nbcbaseball.com.